Noisia AMA - http://www.reddit.com/r/AdvancedProduction/comments/38e8ba/noisia_ama_for_radvancedproduction/

Hackman Against The Clock

KiNK

[quote]The most important part if you start out making music, is to get genre

specific samples from the beginning. This will help you to progress

faster. Many beginners do the mistake to adopt a mindset that they can

only be real if they learn to create sounds on their own, but this leads

directly into struggling, and this is the last thing you want to have

when you just start out.

You must not forget a sample loaded into a sampler can be seen as an

instrument, that can be manipulated with effects until it sounds

completly diffrent and so will be your own. Furthermore you will learn

with the years to synthesize sounds with a synth anyway, and also

recognize that it will still be not easy to recreate a sound if you know

a synth in and out.

But with some good samples which you can use to learn processing skillz

and some production talent you can get quicker to your goal then all

those who are spending more time with finding their sound than getting

something properly finished !

Because at the end its not you who can say that you are original or a pioneer, this will be decided by others for you !

And you can be sure, almost all your hero’s, especially in drum n bass

rinsing sample packs like hell, even those that are seen as pioneers or

originals, but not all really like to talk about, especially which packs

they use, this is a production secret some won’t share.

[/quote]

[quote]The only piece of advice i wish I’ve gotten when I started out, is just

to write tunes and work on the art of writing tunes; full tunes. That

means, if I have to use a sample pack for some elements, just get on

with it and use it. Just work on the most crucial thing which is

arrangement and song flow. Get that down first. Learning details like

programming a break from scratch or sound design would come later, much

later, but at least you would know how to put together a song. Also

write with the intention of releasing music.

That’s really the only piece of “advice” I would give to any new artist.

Get good at writing songs, and write the the intention of releasing

your work. Doesn’t mean you will get releases right away, and for the

most part, your work will suck, but the more you do it, the better you

get. Also don’t listen to naysayers. Just learn from their criticism and

keep it moving. Your work may not sell now, but by the time they do you

will have 50 to over 100 beats to sell.

[/quote]

https://instagram.com/p/3eOf95i8sM/?taken-by=fanufatgyver

[quote=“fanu”]OK, I’m serious about bringing breaks and rich sampling culture back into D&B.

To be honest, I AM sick of hearing the same synthetic sht all over

again, and everybody wants to sound like the next guy. What the fck

happened to jungle? Where’s originality, fresh breaks and beats and

samples?

At some point they took the black element out of jungle, and it became synthetic.

I sorely miss the days when jungle / D&B sounded way more organic.

I WILL start working on the breaks revival movement once I get everything else off my hands (hip hop album being one thing), I swear.

Don’t they says things go in ten year cycles? The last time it was ten

years ago, and we were pushing it HARD, and I loved being part of it.

Need to get back into that.

Here’s something from Danny Breaks, one

of the finest beatlayers jungle ever got to witness; tune called “Mars

To Jupiter” on his Droppin Science label. Listen to those damn drums and

tell me that don’t sound dope as fuck…

EDIT/PS: For the record: I do think Amen has been done to death. There,

I said it. Get off your lazy ass and sample fresh breaks – I’ll do the

same.[/quote]

I like this question but at the same time its like the term composition and maybe compositional skills are semi-frowned upon in e-music (lol sorry) ?

Isn’t all of it just down to compositional skills in an way that inevitably makes the sourcing or the quest for authenticity become a part of the image more than the process?

You could have all the sources in the world and still end up going full-Zimmer?

7 Obscure Mixing Techniques Used by the Pros

Most of the time there’s an obvious choice. Need more midrange? Grab an EQ and boost the midrange. Need more control of the source? Volume automation or compression. Easy. But sometimes we face strange challenges — like how to get more bass in the kick without running out of headroom. Or how do we make something sound brighter that doesn’t have much harmonic content above 7 kHz except hiss. Well, where there’s a will there’s a way. Sometimes the way is just a little less predictable.

So with that said, here are seven counterintuitive mixing techniques you can use to solve unconventional problems.

1. Using a low-pass filter for brightness

What? How can using a low-pass filter make something brighter? Well, let’s say you have a distorted guitar. It’s power goes up to about 5-6 kHz, but after that it’s just noise. A

treble boost will bring out that noise, clog up your mix, and make the guitar harsh.

Instead, use a low-pass filter with a very steep slope. This does two things. First, it cuts out noise and distortion. Second, it actually accentuates the tone at the corner frequency — so while you might be attenuating everything above say 6 kHz (for example), you’re actually boosting the 6 kHz region. This happens because the EQ generates resonance right at the corner of the pass band — and it’s actually pretty clean and clear!

2. Adding midrange for bigger bass

When we want to hear more bass in a bass guitar, kick drum, or other low-end element, the obvious solution is to boost the low end. However, sometimes what we really want to do is just draw more attention to that bass element.

We can do this by adding midrange: pulling up the thud of a kick or the gnarly overtones of a bass. This pulls our ear to that element, telling us there’s more of it there — even if it’s actually just more

midrange.

This can be extremely valuable when you don’t have much headroom, or there’s something else competing for attention in the low end.

3. Using compression to increase dynamics

But wait, doesn’t a compressor restrict dynamic range? Not necessarily. It attenuates a signal that exceeds an amplitude threshold. In most cases that will restrict the dynamic range. However,

if the attack is long enough, and the threshold is low enough, a compressor can actually exaggerate the attack.

This happens because the compressor allows the front of the signal to pass mostly unaltered, while still pulling down the sustain of the signal and making the attack more prominent relative to the sustain.

This can be very useful when trying to bring an already over-compressed signal to life (over compressed … compress it some more!) — or for injecting some serious snap into a dull drum sound.

4. Sharpening transients before a limiter on the master buss

If you’re using a brickwall limiter on your master buss, chances are you’re doing so to make something loud. And to do that, you want the maximum amount of headroom available. So

why on earth would you use a transient designer in front of a limiter?

Wouldn’t exaggerating the attacks use up your headroom faster? Well, yes and no. Technically yes, but remember that these things aren’t perfectly mathematical. Sharpening the transients can do two things. First, you can legitimately get more transient through the limiter and still retain

loudness because a transient designer is boosting in a different way than the limiter is cutting. Second, the limiter is pulling down everything in the mix. That means while your kick hits harder for that 10 ms, your bass gets attenuated for that 10ms as well. The attacks will poke out

clearer in the mix, thus exaggerating the dynamic perception.

Warning: sometimes this sounds like crap, so use it when it works and don’t use it when it doesn’t.

5. Using distortion to make something sound cleaner

Now that really doesn’t make sense. In what way could distortion possibly make something sound “cleaner?”

If we define clean by clarity of tone rather than by purity of the original sound, we can use harmonic distortion to make something sound more “polished.”

Light amounts of harmonic distortion will exaggerate the overtones of a source. Our brain uses these harmonics to tell us what exactly we’re hearing. It’s kind of like saying we’re going to make this clarinet more “clarinet-y” by emphasizing its partials.

6. Using reverb for intimacy

Remember that reverb is used to create a sense of space. Without reverb, it’s hard to define the front-to-back relationship of elements in a mix.

Contrasting wet elements with room sounds to the elements that are almost entirely dry can actually create a more “in your face” effect than simply leaving a sound 100% dry.

The key to doing this is to keep your forward elements sent to a reverb that is a) primarily early reflections, and b) has a long pre-delay.

The other benefit to using this kind of “ambiance” reverb is that it reinforces the tone of the dry signal a bit, which often makes it pop forward as well.

7. Mixing quietly towards loudness

Not that I feel loudness is absolutely paramount to a successful mix, but in today’s climate of

iPods, noise-ridden listening environments, and DJ controlled playlists, it’s important that the record lives within the same general vicinity of apparent loudness.

Or to say it another way: the record shouldn’t sound out of place amongst the other records being played shoulder to shoulder with it in the same genre.

Getting a mix to sound loud without losing tone, dimension, or punch can be tricky — especially when the references of today’s mixes are as loud as they are.

So I’ll say two things. First, trends are showing that the loudness wars are easing off in pretty much every genre except EDM — so aim to make your mix maybe a little quieter than your references. You’ll have a much easier time getting the mix to hang together.

Second, mix your record at low monitoring levels. The reason this works is because it forces you to create energy and excitement when loudness is not an option. This will force you to be more selective about EQ and compression settings, as well as general levels and imaging.

Thomas ‘Take’ Wilson has been building mind-blowing beats since the

MySpace days, releasing albums on labels like Buttermilk and Alpha Pup

and building fans on both sides of the Atlantic. He’s also released

great records as Sweatson Klank, including last year’s You, Me,

Temporary album.

Very impressive, IMO. He not only narrates what he’s doing, but is able to arrange a track rather than just having a 64 bar rolling loop.

Icicle Discusses The Mechanics Of His New Live Show

As a producer, Icicle’s technicality is kind of unparalleled. Poised and

measured he’s impeccably frequencially balanced and ever so meticulous.

In short, his attention to detail is impressive to say the very least.

It’s a style of proficiency that the Dutch producer has demonstrated

consistently throughout his discography of critically acclaimed material

(which includes two phenomenal artist albums, Under The Ice and Entropy,

which were both released on Shogun Audio). The latter work has since

recently been transformed into a brand new live show, thoughtfully

entitled Entropy Live. Described by the Ice Man himself as his

motivation to “bring what I do in the studio to the stage” the live show

promises to be an hour long performance of live sequencing and analogue

mixing that’s channelled through via his plethora of hardware,

controllers all set to stunning visuals that’s hosted by the lyrical

talent of Manchester emcee, Skittles.

On paper, it sounds like it will Icicle at his finest. So to prelude the

event, we hot stepped it over to the producer’s south London studio, to

discuss the inner workings and his motivated intentions behind the

creation of his live set…

Could you give me a brief verbal run down of your studio?

Icicle: Ok, so Logic is by far the back bone for my

studio set up at the moment. I’ve got my soundcard, vocal speaker and

Audeze headphones that are amazing. I’ve got a second screen where I run

my analysers. It’s got this perfect curve taped to it as I worked out

exactly where I want my music to be. There’s also a fair bit of kit here

that I’m more likely to use in my live show. I’ve got Machine Studio

which the whole show is based around. It gives me this higher level of

control and in the studio I’m able to break down my tunes from Logic and

put them into individual parts. My new keyboard, Komplete Kontrol S2

from Native Instruments is amazing. I use it a lot as a fair bit of my

music is made using Native Instruments software. It allows you to see

where your samples are mapped once you’ve loaded up your instruments, or

a complicated contact patch, so it makes the whole process and your

work flow much faster. It’s a really intelligent MIDI controller - none

of the other controllers are really built for this sort of thing. I’ve

got the Virus TI Synth too which I also use when I’m playing live – it

makes everything sound really nice and is a very good thing to use on

the computer with all the DI stuff. So, yeah, I guess this is just the

basics of my studio – I’ve also got my rack synths and modular synths

that I use for fun from time to time.

What’s your favourite piece?

On stage it is the Machine Studio as it’s the core of the whole show. I

also get a huge kick out of the Virus if I’m playing on some big stage

somewhere with a huge sound system. In the studio, it’s difficult to

say, but the speakers give me so much clarity especially when backed up

with the headphones. I cannot stress how important it is to blow your

entire studio budget on a solid monitoring system.

So I read that your live show is really about bringing what you do in your studio to an audience…

Well the basic [make up] of my live set up is what I’ve just shown you,

but I’ve also got an analogue mixer. This runs out of my soundcard and

allows me to mix outputs like drums, melodies, bass and percussion as

they all come in. You can use a mixer on the computer but I’ve purposely

used an analogue mixer so that it’s completely authentic. It’s just me

creating some loops, sequencing, filtering out and creating a

progression while playing melodies over the top – a process that I

regularly do in my studio but is being articulated on stage. It’s me

doing a lot of shit. Of course, I’m not collaborating and improvising

with some jazz band, but it’s more live than I’ve ever been before and

it’s allowing me to connect so much more with my music. You know, I can

mix tunes from my USB stick in a club but it’ll never hold the same kind

of value compared to playing live. Even when you play your own track in

a DJ set, they’ll be some other DJ who’ll play it exactly the same way.

I guess playing live is presenting yourself as an artist in your rawest form…

It’s just more much honest. With the live show, I only play my own

material so if I feel like I’m losing the energy or disconnecting with

the crowd I can’t just quickly play some anthem to get the crowd and

energy back. It’s completely down to you and your music.

Do you find that there are more limitations compared to DJing?

It is a limitation but it’s not [limiting] because on the other

hand, playing live is 100% your own identity. It’s you. I don’t know, I

guess maybe it has something to do with the fact that I feel as if

DJing is too faceless. You just play the best combination of tracks and

although there’s a lot that has to be said when it comes to selection

and working the crowd – you can still be a genius with it – but, as I’ve

come from a vinyl back ground, I feel that the authenticity has gone so

DJing just didn’t cut it for me. I’ve always felt that there must be

more to it.

Can you tell us about the visual element of the live show?

I’ve done a live show before Entropy with an old set up – it

was fun and it taught me a lot but with this show I wanted to explore

and incorporate a visual element. In drum & bass you often see these

overly produced, big budget visuals brought in by some external company

but I wanted to do something a little closer to home. A friend of mine,

Drew Best, who’s a renowned animator from America happened to be really

interested my ideas. I wanted to use my MIDI to control the visuals

myself, triggering various different visuals each time I played a

certain note. I wanted the visuals to underline what I was doing

musically rather than just having some DVD playing in the background.

I’ve also got a VJ to help with the effect and keeping the flow – which I

can’t do because I’ve only got two hands. It’s really fun to think of

your music on a different level and how it can be presented through

visuals. Video is multi-dimensional so I think it gives the show a lot

more depth.

And can you tell us about Skittles, having a vocalist involved must add a whole other ‘live’ dimension…

It’s wicked to have him involved. He’s a massive part of the show and

we’ve worked hard to get right but it’s been a lot of fun to play with.

He comes from more of a hip hop background so we met at this interesting

creative place which maybe before might’ve not have been so obvious.

But it’s worked really well.

What has been the biggest challenge you’ve faced since you started developing the live show?

There have been so many! I mean, just getting stuff finished on time is

challenging enough. I guess what I’ve found to be most challenging is

just traveling with all the equipment. We’re taking about carrying 100

kilos round with us and we’ve only done about seven shows so far.

Setting up has proved to be quite difficult too – every club is

different so there will always be some technical issues. It’s also hard

to work with sound engineers who aren’t used to this kind of set up. And

to be honest, performing is hard too. Compared to a DJ set where you

can get drunk and go with it, you have to really focus so it can drain

your energy a bit though it is completely worth it.

Would you say you’ve found the whole experience quite daunting in some ways?

Realistically? Yes it has. I might know how I am going to perform, how

I’m going to combine the LED projectors and how it’ll all work together

but until you’ve done the whole tour and you’ve experienced every

possible scenario in terms of the different clubs and different people,

there’s a lot of stress that comes with it. It’s exciting though.

There’s not a lot of artists who are doing this kind of live show,

especially in drum & bass and even more so within my particular

sound. So you can kind of secretly go, ‘fuck yeah!’ It’s all worth it.

Do you feel it’s helped you progress as an artist?

Completely. For me to work on numerous different platforms, different

software and to completely think about my music in different way, it’s

definitely helped me progress. As I said before, I might not be some

jazz pianist but I’m thinking about what more I can do in dance music to

keep people listening and interested in my music so I think there must

have been some progress along the way. In fact, in terms of the visual

side of things, initially I was completely new to it but I already feel

pretty clued up. I’ve been learning non-stop for the last couple months.

It’s got me to a place where I am really excited again. Music got to a

point where it became still in the sense that I was doing well for a

while, people liked my music but they didn’t necessarily want me to

progress or do something new so I felt stuck.

I have the most fun when I’m learning new things. I never cared too much

for my tunes or my back catalogue because I was always focused on what

was next and how I might be able to do something different. So I think

the live show has been a major opportunity for me to learn new things. I

now have this feeling that the sky is the limit. What else can I do?

What else can I learn? It’s motivating.

Is there a lot more to come from it? Do you plan to develop the live show further?

100%. This is just my starting point. I’ve proved that it works, I can

travel with it and perform the show in many different places. I imagine

that eventually there will be a massive stage with all sorts of

incredible LED projection mapping and perhaps more people on stage with

me. Ultimately, the goal is to connect with the audience and to make

people want to dance. I don’t want them to think of my show as some

self-indulgent, weird audio visual show so I think I will maintain this

focus on trying to make it work in any environment we’re put in.

So briefly what can we expect? How would you best describe the show?

It’s my studio work flow brought to the stage. The majority of the material will be from my latest album, Entropy,

but I’ll also play a few bits from back catalogue and Skittles will be

bringing his mad energy to the table. Overall, it’ll be a unique

experience that’ll hopefully disintegrate the place!

He says while not even using any kind of absorbents / stands for his monitors. Also, his room doesn’t look treated. ![]() But hey, it obviously works wonders for him, seeing as Entropy is a great album.

But hey, it obviously works wonders for him, seeing as Entropy is a great album.

His setup looks good in this video;

Though not sure how old this studio is. Also, we can’t see the back wall. Monitors are Focal Solo6 Be, which aren’t exactly cheap.

https://vimeo.com/19610612 (older though)

Machine Love: Atom TM

Live from MUTEK 2015 in Montreal, Uwe Schmidt offers a peak into his HD Live audiovisual show.

From nine-piece electro-latino orchestras to the projections of

lime-green computer code that complement his digital techno, Uwe

Schmidt’s live shows have long achieved multiisensory impact. He doesn’t

always perform with a purpose-built visual accompaniment—with Tobias

Freund, for example, he’s focussed solely on wringing hard-hitting

sounds from his machines—but his A/V sets are marked by tight

integration with the music, technical inventiveness and dollop of wry

humor.

That’s especially true of the show Schmidt put together for HD,

his 2013 album as Atom™ on Raster-Noton. To the beat of wildly

infectious techno-pop, a screen above the stage is blasted by abstract

shapes, video collages and a heavily retouched approximation of

Schmidt’s head, which occasionally lip-syncs along with the tunes. The

set is both a time warp to MTV’s '80s heyday and a hyper-contemporary

creation, which not too long ago would have required a small army of

animators and effects experts to pull off. When we caught up at this

year’s MUTEK festival in Montreal, I found out that a range of disparate

technological advancements, from ever-increasing processing power in

laptops to the rise of YouTube tutorials, helped Schmidt, who has no

formal training in video production, assemble HD in-house. After a

short performance during MUTEK’s day programming at the Phi Centre,

Schmidt gave us the lowdown on what’s become his signature set.

There’s a computer just for the video and a computer just for the audio,

basically for running larger parts of the audio. A small controller for

the audio and I normally order a desk and an EQ for the stage.

Is there any audio coming from the MPC, or is it just triggering?

It’s both, actually. Everything’s done with the idea of reproducing

pieces off the album, so the complexity was then: how would I fit

everything into an MPC? And I think it’s impossible to do that, or it

would have been insane to attempt that. So I decided upon reproducing

parts of the album as multitrack recordings from within Ableton and

other more improvised parts, which just happened towards the end of that

track, then run out of the MPC. So I’m basically switching back and

forth between the two sources of audio. And, for example, the second

piece I’m going to play, later on, is entirely coming out of the

MPC—there’s no [computer] audio involved.

How close is this set up to what you used when you were making the album?

Nothing to do with it [laughs].

So you completely adapted all of that for this. What did the album setup look like?

It’s very much Pro Tools-based, it’s all editing work. ProTools is

basically the place where I end up putting stuff together, arranging

music, mixing music. So where the audio comes from is—well, I’m flexible

on that. So I have gear—synthesisers, drum machines, whatever—and I end

up layering stuff in ProTools. So it’s a very, very different process

from what’s here. It’s much less improv-oriented; I play very little,

actually. It’s on-and-off, stop-and-go, letting things simmer a little

bit and then going back to the recording, put it back together, delete

stuff, and afterwards coming back. So it’s a rather slow and not very

real-time-oriented process.

HD was very, very slow coming together—something you’ve been working on for many years, right?

Actually, I had started on the album maybe ten years ago and then

had a couple of technical problems and lost the mixes. I kind of started

to mix it down and lost the mixes twice and then I got totally fed up

with it. I couldn’t listen to it anymore. But I had the unfinished mixes

on my hard disk for like, ten years. I always dragged it from one hard

disk to the next, and every couple of months, maybe, I would listen to

some of it. And then, throughout the years, I actually deleted some of

it. I had no connection to [the original] idea, and I just threw it

away—there were two or three pieces off that recording that still

resonated after, maybe, seven or eight years. But I had changed a lot,

and my ideas had changed a lot, so I decided to adapt them and put them

into something else, which then became HD. So it’s not really

that it’s an album that took ten years or something. It’s more like, I

had tracks laying around and then adapted it into another idea, which

was HD. I recorded the other seven tracks for the album afterwards.

Let’s talk about the visual concept, which is the really striking thing about this set. How did the A/V set get started?

Well that whole A/V project started eight years ago. It came along

when I realized that I was able to program and play audio and video all

by myself, onstage. That was not possible to do during the years before,

when I started making music and started performing 20 years ago. I

always wanted to do that, but it was totally impossible—it would require

a small team of people. I’m not very good at giving orders to people.

Especially with video, I’m very picky about timing and stuff like that.

And whenever I had tried to work with people, it was always—it didn’t

feel right. I always had to tell them what to do, and I don’t like that.

And then at some point, after I had performed for more than ten years

with Señor Coconut—it was a totally different thing, me onstage with ten

people—at some stage I was tired of doing that, of being onstage,

travelling with people, being with people [laughs]. I really had

this strong feeling I wanted to be alone onstage and be responsible for

myself, kind of like a samurai idea. So I was getting really interested

again in playing that type of set and did a little research and found

out it was possible, actually, to do video and audio with a rather

portable set, just by myself.

What had suddenly made that possible? Was it particular technology, a particular piece of software?

Well, laptops, I think—laptops and the fact that the average laptop

is actually able to play HD video. I started to play with my MPC3000,

which basically, all the audio came off the MPC3000 and the audio was

triggering the video in real time. That was how everything started. So

this set is a progression of that first idea. Due to the fact that I

wanted to reproduce tracks off the album (which was not the case with

the first set) I had to include Ableton for sound and be able to manage

bigger amounts of audio data, and of course then I switched to HD video,

which requires more memory and faster computers. So now I’m using two

machines—two computers—to do that.

It’s still necessary to have two laptops, one for audio and one for video?

You know, I don’t trust computers [laughs]. It feels shaky in

general, playing with computers. I don’t like computers onstage. That’s

why, as you see, I don’t really look at them. They could be somewhere

else. They’re not, because I don’t trust them.

You like them within arm’s reach, basically.

Yes. If something crashes, which has only happened, like, once in

three years, I need to be there, to reboot or whatever. So that’s why

they’re onstage. But for the first A/V, where I played with an MPC3000, I

had the video computer somewhere else backstage. I ran it off a

FireWire cable, and yeah, that worked pretty well.

So you designed all the visuals that we’re seeing here?

Yes.

Do you have a background in this kind of thing? How did you get started?

That was quite a regular experience, actually, because I was pretty

sure about what I wanted to do audio-wise and how to solve that. And I

had a very specific idea about the kind of visuals I wanted. So the

option is always, “Do I find that person and explain to them what I

want, or do I try to do it myself?” Actually, when I started to prepare

that set, it took me maybe four months to actually finish the album. And

to finish that production took me six months. That’s because I had to

learn video editing, blue-screening, everything from scratch. I bought

the computers for the set. I bought the whole audio equipment just for

that set and had to figure it out and learn it, and also learn the whole

video side of it. Not only how to play it with the program I’m using,

but also to make the video, to produce the video. So the first section,

for example, of that video, the first seven minutes, are an entirely

pre-rendered section that I trigger off the MPC and the two computers.

So the audio comes off the Ableton, and the video comes from the other

computer.

And they run in sync, fortunately [laughs]. When I first

started to produce it, I wasn’t sure if that was the case. Sometimes

there’s some glitch in the clock and sync or something, and it runs it

out of sync. That’s why the MPC is so important, because the MPC has a

very stable clock and Ableton does not—sorry to say that [laughs].

If Ableton was the master clock for that set up, the video would not

run in sync. So I needed a stable master clock, and the MPC is actually

that. So I started playing the MPC, and there’s basically two MIDI

channels off the MPC. One is triggered with the video and one with the

audio, and they run in sync forever, basically.

So MIDI keeps both the video and the audio in sync—that’s the way that they’re talking to each other?

Yes. So the MPC is starting the clips and switching the

clips—switching the video programs, switching the scenes, the layers and

so on. And every now and then I can play the clips with pads, and

sometimes they’re playing by themselves from within the MPC.

So you’re still getting to play the video? This is one of the big

questions people have about a set like this: when you’re trying to have

video and audio working together, how flexible can you be with the

audio? How much can you deviate from the particular script?

Quite a lot, actually. Maybe in the next track it’ll be a bit more

obvious—it’s way simpler than this one. The question is not so much how

far can you modify what you’re doing; the question is, how much do you

want to? Or how far are you able to do that? Since I started to play

music live, I realized that there’s a certain balance between how much

you could do, and how much you really will do, from experience. From a

very early moment I used very complex machines onstage, and you never

really use the entire complexity it gives you. You always end up with a

certain number of parameters you want to tweak, and after realizing that

it’s much more inspiring for me to have far simpler machines onstage

and just focus on a couple of parameters you want to tweak.

So a track like this, for example—you realize when playing it what’s

possible and what’s not possible. You thought [some aspect of

performance] would be fun while preparing it, but it’s not actually that

entertaining when you’re doing it. So this is how certain ideas ended.

Basically the whole experience for me shrinks down to a very defined

choreography, I would say. You know what you like about a certain track,

you know what works and what doesn’t. And within the whole set, which

is a one-hour set, I have to find the spots to improvise and the spots

where it’s not necessary to improvise. So like I said, the first six

minutes of this track, I wouldn’t have to be onstage, actually—I could

play and just remain onstage fixing the audio and doing little things

here and there. Then it goes into a couple of loops after six minutes.

It gets stuck in a loop, and I can improvise on top of that, and audio

from the MPC is then layered on top, and so on. And then I play some

sounds, which trigger some video. The very end section—the whole track,

if I just run through it and don’t really improvise, it would be maybe

seven minutes, but I’ve played that track for maybe 25 minutes. If the

vibe is good and the sound is good and I’ve realised that people want

more, or it’s just fun to do when I have the time, then I can expand it

quite a lot.

I imagine that’s the important part of doing a set like this—if

it’s too planned, you can’t really react to the crowd. You’re basically

just getting up and pressing play, and giving people the same thing

they’d get if they saw you on any other day. But at the same time, you

also don’t want it to be too improvisational or too open, or else you

probably wouldn’t be able to have such sophisticated things going on

with the video and all of that. Is it a balance?

I think so, yeah. There are a couple of factors here that you have

to start taking into account before making a set. For example, before

performing at a festival such as MUTEK. It’s a very different situation

from performing at a sort of concert, where they invite just you to

play. You could play for two hours if you wanted. At a festival you’re

given a certain slot, and they tell you to play for 40 minutes or

whatever, and then someone comes on and says, “That’s it.” So you can’t

really improvise entirely, even though you wanted to, and you even

sometimes have to take bits and pieces out of the longer set to make a

shorter set.

To me it’s rather important to be able to structure the entire

thing, time-wise, to have an idea for how long it can be and develop a

feeling for it. I’m not looking at the clock when I play; I have a

feeling for it. I know, if I improvise at a certain time, there are some

islands of safety after the improvisation part where I can relax a

little, where it’s pretty structured and I don’t have to worry. I

personally need that structure for that kind of set, because it’s

really, really complex. It’s a very simple setup, but this means it’s

really, really complex, the way to program it—like how its interlinked,

how the media and the audio are different. If you make a small mistake,

like switching the wrong program at the wrong moment, you can mess it

up. So there’s a lot of concentration involved, and making it 100%

improvisation would be a bit too much to focus on.

You mentioned that there are moments where things could malfunction and could go wrong—

And sometimes they do, and I have no idea why [laughs].

Does that happen often? And what do you do in that situation?

You act as if nothing has happened [laughs]. Yeah, it

sometimes happens. It’s quite mysterious actually. Every now and then—I

would say maybe ten percent of shows—there’s a glitch—sometimes a major

glitch, sometimes a minor glitch—where the program wouldn’t change, for

example. And normally I rehearse that; for the technical side of things,

I rehearse before I go on tour. If I change a piece of equipment, or a

cable even, I run the whole set for a couple of days, actually,

emulating the live show. And it’s happened quite a lot that it’s all

identical: the cables are numbered, it’s always the same connections, I

never change the cables, it’s always the same thing, and it suddenly

doesn’t trigger and I don’t know why. I make a note of it, and when I

get home I go back to that glitch, as I want to see what’s going on, and

then it works. It’s weird. This setup is quite, how can I say—I thought

a lot about this setup, and the reliability of these machines, and I

test them a lot and know what could happen and what the possible bugs

could be.

In general I’m pretty prepared, you know? I’m not freaking out like,

“What’s happening?!” It’s always just, “Oh.” There are always moments

in the structure, and there’s moments like this in the whole set: I

start the MPC’s pattern base, and I start with pattern one. Then I run

from pattern to pattern, using the foot pedals—I step through. I never

go back from 20 to 16 or something, it’s all a sequence. And there are

always points in that sequence of patterns where I have programmed a

reset. So if you’re lucky, you’re back on track.

So there’s a little bit of troubleshooting that’s built into the set up?

As much as possible, yeah.

You’ve been playing this set now for about two years, right?

Yeah, two and a half years.

How has it developed over time? Or are you basically doing what you were doing before?

No, actually it has. Like I said before, it took me a long time to

program it and to make it run, and while on tour I can’t really change

anything, because it’s too complex. So what happened is, I prepared the

first version of the set, and then I realised that certain things would

not work, or I preferred a different order, or I enjoy a lot of things

more than others. So I did a second version a year after where I changed

things and took pieces out and put other pieces in and streamlined it a

little bit, I would say. And that’s basically still the version I’m

playing.

I definitely wanted to ask about is this guy [points to spinning Atom™ head on the screen]. We didn’t see it in this portion of the set, but there are parts of HD Live where he’ll talk or sing along with the music. What are we working with here? He’s a computer-generated version of you?

Photoshop [laughs].

How was he created? Did you film yourself?

Well, there’s no 3D rendering or anything involved; it’s playing

with Adobe After Effects and stuff like that. This is just the picture, a

photo. And there’s the other parts where I’m singing. And actually, the

thing for me performing the HD album live is that there are

vocals in there. I didn’t want to perform vocals live—I’m not a

vocalist—but I wanted that connection to happen, that when the extra

voice was sounding, it’s not just coming from somewhere but there’s some

relationship. You see that there’s something happening with the vocals,

something’s happening or someone’s singing or something. So my idea was

more to create a virtual me, basically, that’s singing from the screen.

The inspiration was Max Headroom, actually.

So when I started to produce [the set], I had to produce the videos

and the audio. The audio was really simple—I had done that hundreds of

times before. As for the video I had no idea what that meant. So I

bought the video computer, and I bought the software, and then I had to

learn After Effects from scratch and Premiere from scratch, and I had to

learn blue-screening from scratch. I did the whole thing without

anybody else helping me. One of the very last things I had to do was

actually the head that’s spinning and talking. I wanted it to look

really artificial, but I had no idea how to do that. It was just like,

“OK, this must be possible, but I don’t know how.” So I said to my

daughter—she was 15 back then—I said, “I have to learn the software.

It’s called Adobe After Effects, and I need to learn blue-screening, and

I have no idea how to do that.” Then she said, “Why don’t you go on

YouTube and look for a tutorial?” [Laughs] I was like, “Yeah, of course!” So I learnt all of the blue screening stuff on YouTube.

That’s something I hear all the time from people just talking about

audio: if you don’t know how to use something, you just go on YouTube.

Exactly. And interestingly, when I wanted to start looking into

blue-screening, I thought it would require a small team of people:

somebody with a camera, somebody doing the lights, somebody even for

makeup. It’s a small anecdote, but I was thinking about how to do that. I

was about to buy light equipment and a blue screen. I was standing in

my bathroom, which has this huge open roof, in the summertime in Chile,

so it’s really, really sunny, and there’s this huge mirror. I was

shaving, and behind me there’s a thing to hang a towel. And I’m standing

there, looking at myself. The problem with blue-screening was, how

would I film myself, and how would I see what I’m filming without

anybody else doing it? And I realised that I was looking at the mirror,

and actually the light was perfect. I could hang the blue screen behind

me where the towels go [laughs].

That’s how I did it, basically: I could put the camera in front of

the mirror, so I could see in the mirror myself, in film. And the light

was perfect, and I could put a grey towel behind me, so I wouldn’t even

have to buy the blue screen! But I wanted to see if it worked, you know?

And it worked. I just filmed myself and blue-screened, and I cut myself

out and did all the Adobe work. But to my surprise, something I had not

contemplated before I started was the fact that the video was way

slower and, data-wise, a very, very big task. When you’re making an

album, even if it’s complex work, the session data and stuff is a couple

of gigabytes of production data, you know? Then I suddenly realised

that just filming myself was like four gigabytes. And making a version

of that would be eight gigabytes. So suddenly I had, like, hundreds of

gigabytes. I wasn’t prepared for managing the amount of data, copying

things, rendering things. It started to slow me down. The further I got

into production, the more data I had, and the slower it got. Then the

tour came up. I had the tour already planned and booked and everything,

and the video actually kind of threw me off the plan, and I couldn’t

really finish all the tracks. I used them when I put together the second

version of the set.

How much hard disk space does a show like this set you back?

On the video computer actually, on the day that it’s being played it’s not that big anymore.

Because it’s already been rendered out?

Exactly, so I don’t know—like 60 gigabytes or something. The video

computer is not even a new machine, it’s a four year old Mac. It’s ok,

it’s enough. But also, I’d planned to buy new software for playing back

the video, but I had no idea how that would behave when I configured it

with MIDI. So I bought it, because I wanted the maintenance, the

troubleshooting—being able to call the people and being like, “I had a

problem” or whatever. So I bought and installed it and when I started to

put the set together suddenly it would crash and I wouldn’t know why or

what the problem was. Was it the codec, or the amount of data? So there

was actually a lot of time spent troubleshooting with that and playing

it over and over and over again, until I had the feeling it was kind of

stable. But it was a lot of trial and error and re-rendering the whole

thing in a different codec, finding the right proportion between the

codecs, compression and a lot of data, and so on and so on. In general,

triggering with HD video off a laptop is the tricky thing with that

software. It never feels 100% safe.

I know one of the big technical considerations of this set is

getting the video to the projector and then to the screen without a huge

amount of lag. It’s more complicated than just plugging an HDMI cable

into the projector. What do you have to do to make sure that what’s here

on the laptop is matching up with what’s there on the screen?

There’s a funny story. I went on tour in France last year—it was

like seven shows in a row, every day a different show, and the guy who

booked the tour for me also was the tour manager. And he asked me

before, he said, “Tell me, what do I have to know about your setup, so I

can help you? Is the video very difficult?” And I said, “Well, actually

you will see that every single day there will be a different problem

with the video.” And he said, “No, it’s not possible. It’s a standard.

It’s HDMI, it’s just—you plug it in, and…” And I said, “You will see.”

[Laughs]

I have a couple of things in my tech rider, it’s quite specific what

I need: it’s an amplifier, or an Ethernet transmission system. There’s

not too many options. And then, on the first day, the projector would

not recognise the computer. On the second day, it would be noise

somewhere, and so on and so on. Every day there was a different issue,

and every day it took me like two hours, being patient, talking to the

people. And it’s always the same routine, because the video technician

always says, “Oh, it’s your computer.” And I’m always like, “No, it’s

not my computer, I know it’s not my computer.” [Laughs.] And then

you have to go through it—they go get another cable, and I don’t know,

it’s sometimes the adapter, sometimes the cable or the combination

between the two. It’s quite mysterious, actually. It’s not as standard

as you would think it is. And then every now and then you have huge

latency, where it’s so off that it’s not fun to play. Then I have to

delay the audio on the main board, which makes it really hard to

improvise because you’re like half a millisecond off. It’s a lot of

concentration and trying to have fun onstage, but its really not

comfortable, not smooth. All that kind of stuff can happen and you have

to be prepared for that. And be patient.

You’ve been doing this set for a number of years now. Are you

beginning to think of what the next step is? Do you have some ideas for

new ways that you could perform onstage?

Yes, but it’s not very concrete just yet. This is basically the last

year I will perform this set, and then I have to go on to something

else. I have a couple of ideas, musically and visually, of what that

could be, but I’m not very far with that just yet.

As you’re working on new music in the studio, now that you have

all of this experience with video, does that influence the music making

process at all?

No. Whenever I make music in the studio, I know if I would like to

play that live or not and in which way. Sometimes I think it’s not

always necessary to have video. There’s a couple of sets, like the one I

play with Tobias Freund, for example, without any visuals, and it’s

about a totally different idea; it’s really more about sound than

anything else. And, yeah, whenever I make music I already have the

feeling for whether it can be played live. Not all the music I make

should be played live. There’s different moments in music where it’s

better to just listen to, you know—at home, for example. And not all

music needs the visuals, either. For example, the other piece I’d like

to play used to be an encore for the first A/V set. It was a piece I had

just thrown in very quickly, just in case people wanted me to play

more. It’s just out of the MPC, and [the visuals are] basically just a

very small JPEG, a very simple black and white JPEG. And what I do is,

with the MPC, I play plug-ins on top of that JPEG, and the overload of

the different plug-ins does all the effects. And it was so much fun to

play that I put it in the set and kicked something else out. It’s

actually one of the only old pieces I had to transfer into the new

system, so it’s an entirely different idea, and it’s a piece of music

that very much only exists because it’s so much fun to play with video.

It wouldn’t be half as much fun without it.

NGHT DRPS: Against The Clock

Up next: NGHT DRPS. Although he’s based in Berlin, NGHT DRPS draws

many of his influences from London, often blending elements of grime and

garage into his productions. He’s currently working on an audiovisual

live show, collaborating with Berlin’s visual artists.

For his Against the Clock, NGHT DRPS shows off his hardware-based

approach to grime production, combining the chopped r’n’b of acts like

Low Deep with classic bass and synth sounds from the genre’s early

years. Listen to the finished track on Soundcloud and check out NGHT DRPS’ debut EP SLIPPIN, out now on Through My Speakers.

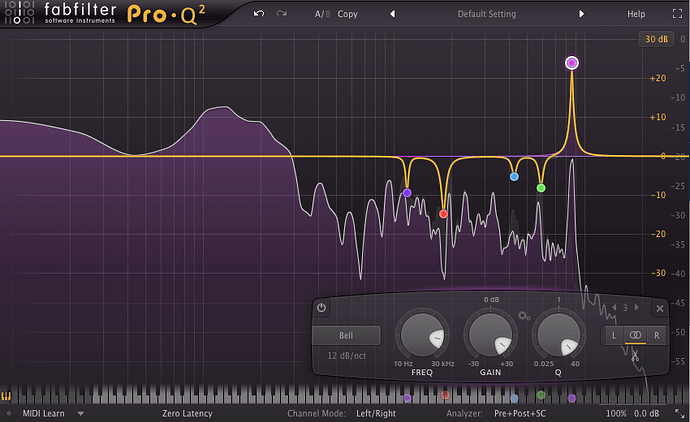

How to find unwanted/ringing frequencies in your mix and carve them out?

It often happens that the sounds we use in music contain a bit

of useless noise that only fills up the bandwidth. Our ears get so used

to hearing our songs, we may not hear these things while we’re mixing,

so this is a good way of removing what’s unnecessary. We end up getting

all kinds of small things with funny resonance in our mix, and

in the end they often accumulate, so it’s good practice to get rid of

’em.It’s easy to find it and carve it out to make your mix more

spacious. This can be done with any EQ out there, but it’s preferable

that the number of bands can be pretty high.

Use EQ bands with narrow Q setting and high boost (see the rightmost

band in the pic), around 15+ dB, to find “annoying”, unmusical

frequencies in your mix. As you’ve set the band to narrow Q and high

boost, “scan” thru the frequency range slowly back and forth, and you’ll

hear it when something starts to really stick out of the mix. Then,

once you’ve found that, simply do a cut on that band, cutting as much as

feels good; it’s usually safe to cut, say, -3 dB, or more but I rarely

carve out more than -7 dB or so, but it’s always case-specific.

Keep the band narrow to not cut too much out of your mix: we only want

to find the annoying stuff, and those badboys don’t usually take a very

broad space frequency-wise (if you find that’s the case, though, you

should go back to your mix). Do this with several bands (as seen in the

picture) until you’ve carved out all the unnecessary clutter out of your

mix. As you’ve found everything, try flicking your EQ on/off to hear

the total result, and you may be amazed how much clearer your mix

sounds. Also make sure you’re not carving out too much; the sound may

get hollow and unnatural if you do.

For me, this is a part of mixing as well as mastering process. I do

it to instruments / tracks, but nothing says you couldn’t have a master

EQ doing this while you work on your song; just make sure to do this at a

later stage when you probably have all the elements in your song you’re

going to use. Loop a busy part of your song for this process. I do a

bit of both.

Resonant stuff or “ringing” is common with old recordings as well as

those made with cheap recording devices, and rooms tend to create their

problems in recordings, too. I tend to use lots of old funk breaks, for

example, and some of them can sound a bit funny, and a lot of unwanted

stuff can be there you may want to notch out. However, it’s good to

realize that some of that can give it its character, and you may not

want to get too “perfect” with it in order to retain its vibe.

As for plugins: Fabfilter’s ProQ2 as well as any sonogram (such as that of Melda Productions’ MDynamic EQ) can be great for actually showing all that resonant stuff for you.

FANU AMA