[quote]It’s been a while since Slices Uncut has graced Electronic Beats TV, but

we knew we had to revive it when we had Chicago legend Boo Williams in

the house. In this series Slices goes deeper in an attempt to discover

more about the artist, and the format allows them to speak their mind on

anything from production to music business. A disciple of Chicago house

pioneers like Larry Heard and Marshall Jefferson, Boo built a signature

driving sound that appeared on seminal labels including Peacefrog,

Cajual, Relief, DJAX and Rush Hour.[/quote]

The Cosmic Sound of LA

Inside the studio that’s shaping Los Angeles’ underground hip-hop scene.

Located in Atwater Village and run by veteran engineer Daddy Kev and rapper Nocando, Cosmic Zoo isn’t the first hub this scene has had – Kev’s club night Low End Theory has been doing its thing for close to a decade, helping cultivate the careers of Flying Lotus, Gaslamp Killer and more – but it plays a crucial role in shaping the sound of the music that comes out of it. In this FACT TV documentary, Gaslamp Killer, D-Styles, Daedelus, Jeff Weiss and many more explain just why it’s so important

https://soundcloud.com/shots-fired-podcast/episode-84-part-2-kevin-martin-the-bug

(unable to embed)

Shortly before the year ended, The Bug (Kevin Martin) stopped by the Cosmic Zoo amidst his U.S. tour for his latest stellar album, "Angels & Devils."Over the last two decades, Martin has cut one of the most singular and innovative paths in electronic music, grime, and UK hip-hop. If none of that makes any sense to you: think the British analogue to El-P.During this one-hour interview, he talks to Nocando and Jeff about moving to Berlin, contemporary music culture, the time he almost worked with M.I.A., his love of The Weeknd, and other great stories and insight from his legendary career.

Listen to The Bug: soundcloud.com/ninja-tune/sets/the-bug-angels-devils-tracks

Follow The Bug on Twitter (twitter.com/thebugzoo)

In this episode – first in a series of videos we have coming up from Detroit – we put Nick Speed to the test, and boy does he pass. Speed has released on Mahogani Music and Underground Resistance, while producing beats for everyone from Lloyd Banks to Danny Brown, and as he demonstrates here, he makes tracks FAST.

So fast, in fact, that he actually makes three beats in the timeframe, and raps over them. It’s pretty incredible – check it out above if you don’t believe us.

FJAAK are a techno trio from Berlin who’ve been steadily releasing singles and EPs since 2012, most notably on Modeselektor’s 50Weapons label (which recently closed its doors.) They all live together in one hell of a studio and basically just make music all day, which is a beautiful thing. They also have a dog, which pops up a couple times in the video. That’s also a beautiful thing, we’re sure you’ll agree.

Last week we released The Cosmic Sound of LA, a documentary on Daddy Kev and Nocando’s Cosmic Zoo, studio and key physical hub to the city’s underground scene.

As a companion of sorts to the video, we quizzed Kev on the studio’s set-up, his approach to EQing and compression, his opinion on the loudness wars and the different eras of music mastering. As anyone who follows Kev on Twitter will know, he’s full of knowledge and advice when it comes to music production – for budding producers this is a must-watch.

Legowelt has been putting other house and techno producers to shame since the the 1990s.

The Dutch artist releases music at a rate of knots – there’s been at least nine albums under the Legowelt name alone now, and he has over 30 different aliases, all of which interact in weird, wonderful ways. His music has appeared on labels as disparate as Unknown to the Unknown and Cocoon, and he’s got a reputation as a real studio wizard – not only due to the hardware in the studio, but the sample packs and plugins that he gives out for free online. On top of that, he’s about as unpretentious as it’s possible to get.

In this video, FACT TV and DJ Haus – who, as previously mentioned, has released Legowelt records on his Unknown to the Unknown label – get to watch Legowelt make a track from scratch, using a combination of his own patches and sample packs, a tape player and more. It’s no surprise that he makes it look easy, is it?

Dubplate Culture: Analogue Islands in the Digital Stream

The era of dubplates is gone, despite a collection of reggae soundmen continuing the tradition. Matthew Bennett writes about its heyday, its demise and what we’re missing as a result.

“It’s completely dead,” grimly mourns Dillinja from behind his drink. “Dubplate culture has died.” The drum & bass producer is sitting with his business partner of Valve Recordings, Lemon D; a pair of men who once guided the flow of the drum & bass scene. They are performing a rhapsodic autopsy on the crucial role of dubplates in evolving dance music through the ’90s as jungle mutated into drum & bass and then into the ignition of UK garage.

“Dubplate culture defined you as an artist,” adds Lemon D, AKA Kevin King. “It was always more than just cutting the actual plate.”

Often mentioned but rarely discussed, dubplates were once obsessively crafted musical artefacts that both controlled and evolved music scenes. “There are parts about cutting dubs that I really miss. Then there are bits of it that I don’t,” murmurs DJ Hype as he drives us through East London after broadcasting his Kiss FM show. “A dubplate is a one-off pressing of a record that is made out of acetate and metal,” Hype explains. “It was the cheapest and best way of being able to play a new song on a soundsystem or in a club. So back in the day you had two choices: you could come with a cassette or you had the dubplate. It’s a way of testing out a song, but the Jamaican soundsystem clash culture started using it for more exclusive public performances for a one-off song that no one else has got.”

Dillinja’s diagnosis of the scene being dead rings true for any producer or DJ except those in reggae. Jamaican selectors may still cut “specials” which reference a rival’s name, or perhaps they cut a dubplate after persuading a legendary singer to mention their own soundsystem at the start of an anthem for killer prestige in a sound clash. But where the lathes once produced a week-long torrent of innovative music, now their output is just a revered and treasured trickle of reggae re-rubs. The jungle, drum & bass and garage producers are no longer found here anymore.

Dillinja remains exasperated by the loss of dubplate culture to digital: “I severely miss the benefits of holding back music. Our best music was held on these metal discs. You paid to get them made and no one could copy them.” The producer shakes his head, then continues, “You’d only give copies to certain DJs that were on the right level. It’d make people want it more! These days music isn’t worth anything.”

Lemon D chips in with a point of his finger: “It was a bit like gardening: you plant a seed over here by giving a DJ a dubplate, he’d go and play it out, and then a few months later it’d be growing its own little scene over in this corner.” Anthems would evolve over a few months across a succession of dubplates, each tested out all weekend, then refined for the next cut. It’s the same way football teams develop training ground set-plays in which a complex strategy is enacted dozens of times before it’s unleashed in a public tournament. Once the finished vinyl pressing was sent to shops, dance floor dynamite was normally guaranteed.

Lemon D remembers the rich era of the mid-’90s when jungle was huge and Goldie’s label was king: “Metalheadz (the label) was right time, right place, right sound. You’d go down to Music House (a popular Jamaican-inspired cutting studio in London), and it was a little social club where people would experiment and cut dubplates for each other. It would define where the music would go in the next couple of months. You’d still be there at 9 PM clinging on to get a dubplate off someone even if you thought you might be missing your gig. You can’t get that now.”

At cutting studios like Music House or Tubbys, these plates would cost anything from £25 to £45 depending on whether they were 7-, 10- or 12-inches. Bigger DJs like Hype – if he was particularly busy – wouldn’t have all day to queue at the more social cutting studios, so he’d spend anywhere from £50 to £90 at the more upmarket Heathmans or Metropolis.

“It’s amazing looking back how much I must have spent,” muses DJ Hype. “You really had to choose carefully. It’s what we called the ‘shit filter.’ Now this ‘shit filter’ has gone. If you had to pay £35 to upload just one song to Soundcloud, then the quality of music would be a lot better. Now anything can exist. And if you went to Music House to cut a DAT of music that was THAT shit, then we’d all be telling you off for even cutting it! It would never get to the dance floor.”

Cutting houses naturally became crucial industry watering holes. They existed alongside record shops like Soho’s Black Market or barber shops like Fish where the inner circle of the exploding jungle and drum & bass and – later – UK garage scenes would meet to discuss their nocturnal work. On a Thursday and Friday, all the different species of DJ would descend to cut dubs, socialise, reaffirm their place in the community, network for the latest tunes… and occasionally even fight.

“Music House was a hierarchy,” affirms Hype, “Even if you dropped off a DAT to be cut on the Monday, if you turned up on Friday it would still be sitting in a pile waiting, so you had to be there to get it done. There was a little waiting room there, and people like myself and all the regulars would go in pretty bullish and make it happen. Newcomers would get put in the waiting room and it was like, ‘Just sit through there and we’ll call you when it’s your turn!’”

But even the big fish like Hype would get nibbled by bigger fish. “I got that with (DJ Jah) Shaka. I’d turn up and need to cut a few dubs but Shaka’s just arrived and he needs to do 20 and I’m like, ‘Jesus! I’ve got to go!’ Now, I would never try to NOT have Shaka trump me. But it’s like Bob Marley turning up and you having a moan at him, isn’t it? You just need to step aside and let him get on with it. Although the reggae boys were there long before us, we all fitted in with a hierarchy. They aren’t going to get pushed about. When jungle got massive it was about 80% jungle producers and 20% reggae each week. But it depended who was over from Jamaica.”

Hype’s memory underscores how multicultural the cutting house was. “Back then you’d never get a quiet white guy from Reading getting matey with a dread from Jamaica. And you know what? You realized that everyone is not really that different. You might speak different or look different, but you are all on the same page.”

Many relationships and collaborations were borne from standing next to like-minded peers. Hype’s work with J Majik was a direct result of loafing about for their turn at the lathe. However with such a strong queue culture of lively characters, things often got spicy. “I used to describe it as a ‘schoolboy playground,’” explains Hype. “We’d all be waiting in this alley in a queue, and whilst we’re all into the same music we are all rivals really. I’m a DJ: you’re a DJ. Sometimes it would get quite divided. I’d always get into trouble because I’m a big gob. Before I’d go in, I’d say to myself: ‘Right! You are going to go there, sit quite, cut your dubs, don’t get wrapped up in any bollocks’ … but you can guess what always happened.”

The chaos and proximity of ears and egos also formed an organic and honourable police force against copying, as Lemon D elaborates: “You didn’t have plagiarism going on. You could cut almost anything musically and it was accepted in that community as the future, and everyone respected that. Back then you could differentiate an artist’s work. You’d be inspired by what you heard there but you’d never steal it like how people do online now. It’s hard to develop a signature sound when everyone has the same tunes. Now everyone has every big tune the day it comes out.”

The culture of cutting and sharing dubs was an addictive and closed network. So it wasn’t long before Dillinja and Lemon D decided to do the unthinkable: to get their own lathe. It was a move that – in hindsight – dragged them through a very long and expensive technical journey. “We got the lathe just around the time when we shouldn’t have gotten the lathe!” laughs Lemon D with nostalgic despair.

The Neumann VMS-70 cost them £20,000 second hand. It was old and riddled with a few mind-boggling issues. Their age meant that many parts were discontinued. (In fact, Metropolis Studios set up a secret foundation whose sole purpose was to gather together elusive parts and materials to preserve their service for an inner circle, much like how Polaroid film was once shepherded around close-knit photographer circles.)

As Dillinja continues their fable, it was clear that the pair had gone in over their heads: “We wanted one for years but when we FINALLY got it then it was just a nightmare, it was all set up wrong. It came in and just ruined everything. Towards the end we really grasped it, but then it was too late.” Nonetheless, for a brief moment, Valve Recordings had a dubplate lathe, a great DJ roster and a massive 96k soundsystem custom built for D&B shows.

Such was the demand for dubplates, and such was their reputation as great producers, that they soon had a very stressful situation on their hands. Here, the pair seem overcome by history as they excitedly remember the joyous pain of their lathe. Lemon D is gesticulating about sliding pernickety circuit boards in and out of dusty slots, while Dillinja rants about broken needles and the depth of a cut. They both still seem mildly terrified of the complex machine they sold a decade ago.

“The head blowing up was bad! That cost us £3,000 once,” exhales Lemon D ‘Then you’d get some dodgy acetates, with bubbles in them. Dubplates are reject plates used for final mastering, so they had imperfections. If you didn’t spot them, these pimples would break the needles, which were £40 new. You’d spend so much money just making mistakes. The circuit boards sometimes would get funny. These boards ould be dry. Remember they are six decades old, so if it was cold it just wouldn’t work!”

Lemon D sits back in his chair: “You’d book someone in, and you’d be there pressing the button repeatedly and the machine is like: ‘Nah, I’m not going to work today,’ then the next person would turn up. Still nothing. Or you had people trying to talk to you and you really had to concentrate to watch the gas. You had to have helium to cool the needle and someone like DJ Hype would be having a full blown conversation with you. This would cause you to make mistakes. So what should have been a £200 session costs you £400, and you’ve made no money. Occasionally you’d blow the head. That cost £8,000 by itself, even when it was broken! There’s only a handful of people in the world that can still fix them, so you’d just send it off to America and just hope the guy was legit.”

It didn’t stop there either: Suddenly Valve required artists with a bit of bedside manner. “Some producers would put in too much top end, or their mix downs were BAD,” cringes Dillinja. “Then you as a producer had to tell another producer that their work was a bit dodgy! They didn’t like that.”

In 2014 the baking hot efficiency of the Internet and its multitude of streaming sites has evaporated any need to visit the cutting house oasis. It’s a redundant, slow moving and expensive museum for anyone aside from the most calculating of reggae soundmen. Looking back, though, it took dubplate culture a bizarrely long time to die. Hype, for one, has adapted effortlessly. When we meet the 45-year-old at Kiss FM he is smashing out his radio show using all sorts of modern technology. But he remains wistful. “Dubplates were CRUCIAL to my development until the digital age. That was the death of that marketplace. I held on till 2010. But if you were a stranger who pulled up outside Music House when jungle was at its peak, in the mid to late ’90s, you’d learn something. You’d see ten BMWs and Mercedes all parked up. And I knew all of those guys when they had nothing.”

As Hype lets me out of his equally plush car 20 years later, the veteran DJ, label owner and producer reflects on that time period one last time: “Back then it was a smaller scene. It WAS special. I didn’t go there thinking, ‘I’m special,’ but when I look back, I suppose we were. We all came from nothing. We’d all learnt that and we’d built up a style of music and culture and being parked outside Music House showed that we were doing good, that we had made good of our

lives. I do miss that reassurance.”

“Am I completely wrong”

I will say I’d stop thinking like this early on, it’s so damaging, there is so much culture of getting things right, especially on places like this.

Get on with it, get it finished, move on, get it out there, enjoy it or shelve it - in a short time, if you have anything going for you, you get better at finishing stuff & better at critically listening to your

own stuff.

or before long you have got 9 million loops & haven’t finished anything for years for fear of being “completely wrong”

Where can I self promote?

Ok, so this seems to be an issue for a lot of artists and it’s something I find that people get wrong more often than not. What you are really trying to do is digital marketing. This means you need to have a strategy, and you need to understand that this isn’t as simple as just posting links to your tracks all over the internet.

The fact of the matter is that there are millions of people online who are trying to promote themselves as musicians. Spend 5 minutes on twitter and you can quite easily get spammed by over 9000 budding hip hop or edm artists prompting you to check their new beats and spamming every motherfucker on their ‘following’ list with soundcloud links.

Simply put, this is not the way to do things. It’s essentially spam and it offers no incentive for users to click the links. Sometimes people can generate a lot of ‘listens’ this way, but they are low-value, as the people who clicked them are essentially complete randomers who don’t necessarily have the slightest interest in the music.

here are a few general tips for approaching online promotion:

- engage with like-minded communities online. Don’t just go to a forum and make a post saying ‘look at my beats yo’ before fucking off. hang around, get involved in discussions, get feedback on your work, give feedback on other peoples’. do all of this with a link to your work in your signature or something. if people are interested, they will click it.

- make a twitter account. follow people who inspire you and take part in, or start interesting conversations with like-minded people. don’t tweet everyone telling them to go to your soundcloud page. put it in your bio and let them find it themselves. tweet at least once a day about your music and about relevant topics that other people might actually be interested in. post links and use hashtags in these daily tweets.

- remember, the best way to advertise anything is not to interrupt someones day by shoving a link in their face. It’s all about giving people meaningful experiences and contributing something to their day, while allowing them to engage with your content as a part of this experience.

If there was a place where you could go and promote your music by sticking links up with no other content or incentive, without anyone bitching at you for it, i can guarantee it would be completely saturated with people doing the exact same thing. nobody likes being advertised at - the only people there would basically all be people throwing shit at a wall. you would be a drop in a shit-filled ocean.

Mostly taken from or because of here - http://www.dogsonacid.com/threads/i-just-got-a-emu-6400-classic-for-cheap-what-am-i-getting-myself-into.773098/

Karl in those days is the perfect example of embracing imperfection. There are various clips of him online when headz was still considered futuristic and forward thinking of him producing. He mashes everything through hardware compressors, desks, and samplers. The Desk is just bleeding noise through the input and instead of spending hours downloading dodgy copies of OZONE or hundreds on wiring and different equipment he keeps it in for character.

Another producer that interests me a lot who took abusing equipment from a different angle is Surgeon aka Anthony Childs. his output from around 1995 - 2004 is some of the roughest techno/dance music out there…

This track is perhaps a better example of minimal than Robert Hoods early works. The drums from 2:00 and on are so simple but so roughly processed. You can hear all these imperfections and noises.

Similar approach to drums except ith metallic percussion and dissonant fm sounds covering the track. The Pad sounds around 2:20 are amazing. It sounds so simple and rough yet far more futuristic than Noisia or Mefjus ever have (I am using them because I have heard of them taking

months to produce a single track).

After hearing some of the digital equipment from the 90’s in record and seeing prices it feels like if you buck the warm monosynth or old mpc trend you have access to some amazing equipment. I could probably buy a mixer, several digital synths, and an amazing sampler and make full tracks before alot of the minimoog and eurorack buyers take out their loans… Trends will be trends though… In 5 - 10 years Emu 6400’s, various digital synths, and mackie mixers could reach the thousands because of some shit techno and tech step revival movement. Then I can buy the rock bottom priced Korg remakes from the trust-fund indie-disco producers.

"An analog synth I almost sold to someone on here for £500 is now going for up to £5,000 … That’s just in a few years … I think digital trends are harder to predict

Re: that Surgeon sound – metallic, crunchy, synthetic … It’s been a long time since I had one, but from what I recall, it’s an auto-wah/distortion effect from the Ensoniq DP/4++ … One of the only fx units he used to own

They’re very collectible now, but the cheap way to buy that effect (and a way I know has that preset) is to buy an Ensoniq ASR10 or ASR10R sampler … It’s right there … Dave Clarke used 2x ASR10s; Autechre are big users … It’s this one very distinctive effect – I think there’s a basic effect chain preset, like Dist/Auto-wah/filter (or something like that), and a variation which instantly turns your House loop into pure Surgeon … A very different sampler from the Emu … Emu sounds like Dillinja; ASR10 sounds like Autechre"

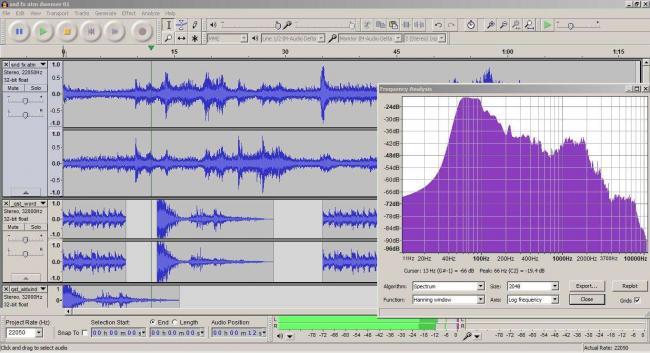

Wondering whether I can use an old laptop I have lying around as a very crude resampler, using the headphone output and the mic input to run samples back into themselves via an SP-303.

Thinking of loading a sample into Audacity, then playing it back/looping it, whilst at the same time setting the record in Audacity to be from the mic input.

So the mic input will record in on a seperate channel, which can then be soloed. Only issue would be that any recording would include a dry signal of the original sample itself…which could give some phasing sounds which might sound amazing or shit depending.

All this will be done whilst messing around with the effects on the SP-303. Could give some interesting drone pieces if nothing else, plus would bring a massive amount of noise into things due to the crappy onboard input/output being used.

The new generation of kids that are having these kind of epiphanies are having them in different ways. They’re probably having them via the internet. That’s cool as well. It’s not as visceral and I don’t know if the impact is necessarily the same but that’s just something you can’t argue with. That’s just the way the world’s gone.

I get the impression that promoters these days don’t want to piss off their crowds. I understand that, if you’re charging £20 to go to a night, you want these people to have a good time, but also I think you need to challenge your audience. And I don’t think that promoters are that interested in doing that. I mean if I was to put on a night, I like the idea of giving the audience something that they probably doesn’t want to see but I think they should fucking see. A good example of that is a few years ago when Russell Haswell curated a night in London and had Whitehouse play before or after Aphex Twin, something like that. LFO might have played as well, but putting Whitehouse on at completely the wrong time – they went down like a sack of shit but I think that’s something that people need to do. Promoters need to take more risks with festivals and club events.

If I’m playing a gig I don’t want to be playing with a whole bunch of artists that do a similar thing to me, I want to be playing with all sorts of fucking people. I wanna play with rock bands, I wanna play with techno artists, hip-hop artists. Otherwise you end up in this stale ghetto. I do wonder how many promoters these days, especially ones who do it for a living and especially the ones who organize these big festivals and big events, I wonder how many of them go to just regular nights as impartial listeners, just for a night out. Get fucked up and just enjoy the night. It’s understandable because it’s the field they work in, but it’s the same thing I was saying about people listening to experimental music – you start analyzing it a bit too much. Maybe some of these promoters just need to go to a club night they’ve never heard of before, take a shitload of MDMA and go fucking mental.

http://tr-33n.tumblr.com/post/123922777056/treen-interview-april-2014

We first came across TReen a couple of months ago through mutual friends and were instantly blown away by their vast hardware set up, their open minded attitude to music production, incorporation of mutant sounds, and of course their celebrated live performances. We’re thrilled to have gotten a chance to interview both Dave and Lou, learning more about TReen and their approach to music!

IA: Okay so the first thing we all wanna know about is the set up! What’s striking about the stuff you guys do is the amount of hardware you use – I know the likes of Karenn and TM404 share an extensive love of hardware, along with British Murder Boys and innumerable others, but the scope of what you guys have is very impressive! What’s in the studio?

Lou: Where to begin?!

The set up. Two samplers, one each – a Korg ESX and an MPC 500; a changing line up of synthesisers, at the moment it’s a xox box, an Access Virus Ti and a Bass Station 2 (but we’ve had a Moog Little Phatty, Yamaha TX7 module and a Korg Volca Keys along the way and just about to swap the Ti for a Snow); effects boxes – a Korg Kaos Pad and an old Echorder. All of this goes into a MIDI patch bay so all the machines can communicate and keep in time by running off the same MIDI clock – which is provided by the ESX, so that’s the start of the chain. All the signal goes into a 14-channel mixer, with the ESX kick drums being split off into their own channel. Finally the signal from Auxiliary 1 on the mixer goes into a 266XL DBX rack compressor to form a side chain compression, and that has its own channel on the mixer as well.

The stay-at-home MOTHER of them all is the Roland TR-808 which doesn’t come out to play (oooh except once! – when we played a set on Al iLLEagle’s original Terrahorns. We’ve sampled the fuck out of the 808 and use the noises through the ESX cos them lush ESX valves mean the sound is reproduced really faithfully to the original.

IA: So how long have you guys been making music together, then? What were the beginnings of TReen?

Lou: We’d been making music together since 2010 as Emily Davison vs The Tigerforce. Dave kicked it off when he bought the Virus Ti, I thought he was mad to spend so much money on a synth and then I heard it. It was just one of those Damascene moments; they don’t come around often, so you should grab them when they do. I was like, “Eeep! We’ve got to do a live set!”, there was no question; it was just obvious. We changed the name to TReen a couple of years later – because it would fit on flyers better basically! The capital “TR” is a homage to the studio backbone of our set-up, D’s modded Roland TR-808 drum machine. He bought it before we got together, back in the mists of time when 808s were neither as fashionable nor as expensive as they are today.

Dave: I’d been noodling on computers since all my old hardware packed up thru over-raving around 2003. When Lou suggested it, I thought, “Let’s do this properly”. I already had the 808 from a chance offer from a mate in Rotterdam but I didn’t really play out with it.

IA: What’s the least amount of gear you have done, or could do a show with?

Dave: It depends on the show, it’s useful to have two sequencers that you can mix the beats back and forth between like a traditional DJ set-up and then anything else can be patched via our midi split. We have a machine dedicated to the sub (Bass Station 2) and it’s good to have a couple of other synths on hand if one goes down, I bought a TX7 for £60 that exact reason and we’ve used an ipad in a similar way. Computers crash, hardware fails, that’s just life.

At one of our early gigs my MPC500 was placed dangerously close to a proper oldschool 70’s bass guitar amp belonging to the hardcore band ‘100% Beefcock and the Titsburster’; the magnets from the speaker drivers totally wiped the flash memory leaving me with only the midi data (stored on the ROM, geek fans!) so Lou had to basically do the gig on her own whilst I played the occasional live bassline from the Novation (BS1) and a couple of midi patterns. I had a Wavedrum that I hit a bit but they’re pretty shit-sounding so I held back out of embarrassment. But an ESX and a x0x on their own can still provide some tearing acid and Lou fucking stormed it. I still had an annoying hippy come up to us afterwards and tell me that we weren’t really playing live because they weren’t real instruments – despite my actually playing live on two instruments.

https://soundcloud.com/tr33n808/4-trax-for-electro-skankin

IA: It could be said there are advantages to having a laptop in a live setting, was the move to hardware prompted by anything in particular?

Dave: I started on hardware in the late nineties because computers couldn’t do very much and were really expensive, I yearned for a laptop so badly and got one in about 2001. It had 128mg ram and ran Reason ok but not well enough to trust dropping stuff in and out live.

There is so much freedom with laptops nowadays, they are amazing. You can design tracks so they can be mixed together and never be performed the same way twice and Ableton seemed to get its shit together after version 7, as did the reliability of usb connections for controllers but it’s not the same as having a buffet of sound machines. I find latency thru usb can still be a bit looser compared to the feel of analogue especially on knobs and sliders. Basically, I think analogue signal is a glorious thing, it IS the sound of electricity and I love that fact.

Lou: I always wanted to do a hardware live set because DAW’s do my head in; I found them really frustrating to use when I was first working out the basic architecture of electronic music. Using the ESX-1 changed all that; maybe I’m just a tactile learner or maybe I just like flashing red buttons, but I learnt more about how decent tunes are structured from having to work from within the confines of the ESX’s framework than I ever managed when I was faced with a blank screen song file: I just never knew where to start. Plus, if I am being brutally honest, I think that when peeps play out on laptops they look a bit like they’re doing their accounts.

IA: On average, how much preparation goes into a performance? Are there pre-programmed sequences that you save beforehand, or is it allcreated from scratch?

Dave: When we play live we have two sequencers running a maximum of an 8 bar loop (usually 2 or 4 bar loops to keep the sequencers running to the same bar count) then everything is punched in and out live, either on mutes or faders on the desk. One song can have 20-30 layers and the combinations of each layer provides the build ups and drops. We try to keep key elements to certain pads (top right pad on the mpc is always the sub on the bass station for example,) so if it is dark or we are a bit confused(!), there are areas to ground or remind us what could happen next.

Other live tricks we use if we’re feeling confident, is the playing of improvised parts on the synths or messing around with the analog delay echo in a dub style.

Lou: A decent monitor set up is our main requirement as we tend to spend the first 10 mins in a blind panic troubleshooting the mix. When possible, we use the teknival method of playing in front of the rig and just using it as a very big monitor: best fun ever.

IA: You’ve got quite an eclectic output, we’ve seen you hammering out acid techno, footwork, even stuff with a real ska swing to it – I’m guessing when you guys start making tunes it’s an anything goesapproach? Or do you tend to focus on a specific sound or sounds fromtime to time?

Dave: We’ve always been committed to getting people up and dancing. We’re both always listening out for samples and things we like that we can incorporate into the set, be it a style, a sound or a trajectory. It must be spirited in some way. No imitating – stealing outright is fine

though ![]()

Lou: Haha! It’s not stealing, it’s just re-contextualising stuff and bringing it into the unique hardcore/breakbeat folk tradition of the UK!

IA: If, for some reason, you had to abandon your entire record collection and could only save three items what would they be?

Dave: In the apocalyptic scenario of which you speak I think I would leave it all behind and just go on the rampage until I met with a swift death.

Lou: Haha I stupidly lost/gave away all my records to random people in a squat I was living in just off Old Street in 2003 because I “…didn’t want to be tied down to earthly things”. Perhaps if I could

just have Rah Digga’s Lessons of Today back? That would be great. Cheers. ![]()

Links:

Music:

https://soundcloud.com/treensounds

http://treen.bandcamp.com/album/4-trax-4-electro-skankin

I fucking love Tr-33N

Few threads on live setups, with a techno leaning bias

New Producer - Looking for a cheap hardware setup

Karenn/ Blawan techno production techniques

Hardware Setup for Techno (live and recording)

What would be a decent/cheap/basic hardware setup for acid/live production?

Mostly taken from here - Reddit - Dive into anything

i thought this was gonna be links to github repos! srsly tho, nice fuckin thread!

Fuk, that second Surgeon track in nice!

yes, thx wubasco sauce

Benjamin Damage hails from Wales, but has settled in Berlin – and when you see his studio, you’ll realise why. He first broke through making tracks with DJ Venom, but settled into a solo groove around 2011-2012, releasing a run of records on Modeselektor’s 50Weapons label. In 2013 he released his debut album on the label, Heliosphere, and will release the last ever album on it, Obsidian, on September 25.

Two generations of UK dance innovators pick each other’s brains.

Loefah has helped to change the sounds of UK underground clubbing twice, first with DMZ, the dubstep record label and club night that he ran with Mala, Coki and Sgt. Pokes, and then with Swamp81, a label that drew from 808-driven electro and hip-hop in a dark UK club context.

Fabio meanwhile has been a presence on UK radio since the mid-80s, eventually becoming recognised as one of the most important drum’n’bass DJs. Before jungle happened, however, Fabio and his long-time partner Grooverider were residents at Rage, a central London night where they championed early acid house and the sounds of Chicago and Detroit. It’s this era that we focus on: the interview takes place at Heaven, before Fabio and Grooverider played a “classic Rage set” at Swamp81’s Carnival takeover of the club.