10 Tips From The Pros

In my opinion, music production is a learning process that never stops. There are always new tips to try out, new tools to get to grips with and new ways of approaching the art of making music. Whilst the natural reaction to this is perhaps frustration, dig a little deeper and you’ll discover an exciting world of possibilities, where there is no set way to do things - all doors are open.

Alongside the vast helpings of online tutorials to aid your learning (including amongst the pages of this magazine), I find that exploring the workflows of others can often have a direct impact on how I make music. It is for exactly this reason that I love watching interviews with my favourite music producers, as typically I come away with a trick or an idea that I’d never thought about before.

Today, I’d like to share 10 such nuggets of music production wisdom with you, taken from video interviews with a number of the finest music producers from across the spectrum of electronic music. The advice shared ranges from the directly practical to the more philosophical, both areas of which I think are incredibly important to nurture in the development of your music production technique. So, whether you’re carving out a niche in the Dance world or pumping your energy into Hip Hop, I hope you’ll find plenty of inspiration below. Dive in and enjoy!

- Four Tet: EQ with Care

In this Pro Tools walkthrough of two tracks taken from his album,

There Is Love In You, Four Tet describes how he achieves his signature warm, organic sound. Defying conventional wisdom that plugins and analog hardware are the route to achieving such a sound, Four Tet calmly reveals that he simply makes sure not to EQ out too much of the spectrum on individual tracks.

Of course, this depends on the sounds and samples you are working with having desirable frequencies in them to begin with, but being careful about what you remove from your sound is worthy advice indeed!

- RJD2: Create Richer Drums with Copy & Paste

Hip Hop producer RJD2 shares his top tip for creating a chunkier kick sound in this video. His technique goes something like this: find a sample you want to work with as your kick, copy it, transpose the pitch down, low pass filter the sound, crank up the resonance and mix back in with your original sound. Simplicity itself!

RJD2’s trick works wonders in adding a rich, phat quality to his sound in minutes. Be sure to try this one out on other drum sounds too, from snares and claps to hats and toms.

- Kirk Degiorgio: Subtle Processing Can Have a Big Impact

UK Dance music legend Kirk Degiorgio is a heavyweight in the world of music production. Here, Kirk treats us to a DAW walkthrough of one of his tracks, demonstrating the effectiveness that light applications of processing can have - in this case, compression on a drum track.

An easy mistake to make as a beginner producer is to assume that piling on the plugins and cranking the processing will automatically make everything sound better. Kirk shows us in this video that applying only 1 - 2 dB of gain reduction can have a big impact on the excitement and energy present in a track. Genius!

- Kode9: Start with Something Simple

Beginning a new track can often be the most frustrating point in the journey towards a completed production. In this Ableton roundtable discussion, Hyperdub label boss, academic and producer Kode9 unveils his top tip for getting around the terrifying ’blank screen’ roadblock - begin with a sample and build your tune up around it. I’ve never absorbed advice so simple and effective since!

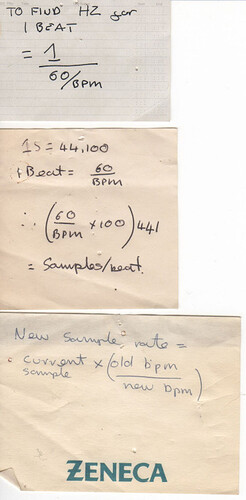

- Carl Craig: Pay Attention to Your Sub Bass

Making sure your kick sound has a nice punch at around 100 - 120Hz is pretty essential in creating a satisfying drum track. However, Detroit Techno legend Carl Craig reminds us in this interview that the sub is often what really matters, both in your productions and in the club.

Taking an EQ and applying a subtle boost to your kick (or ‘foot’, as Carl logically terms the sound) at anywhere from 60 - 100 Hz to bring out that ‘boom’ can work wonders for a track - making sure the right frequency is enhanced is vital, however (check out my tutorial on finding a kick drum’s fundamental frequency for a more in-depth look at this technique).

- J Dilla: Produce When You Feel Inspired

J Dilla is still the king of Hip Hop production for many and his music continues to inspire and educate years after his untimely death. In this rare video interview, he discusses a wide range of subjects with infectious enthusiasm, such as his motivations for making music.

The interview is peppered with inspiring words for producers but my favourite is, once again, wonderfully simple - don’t force your creations and produce when the mood takes you. Long-live J Dilla’s influence!

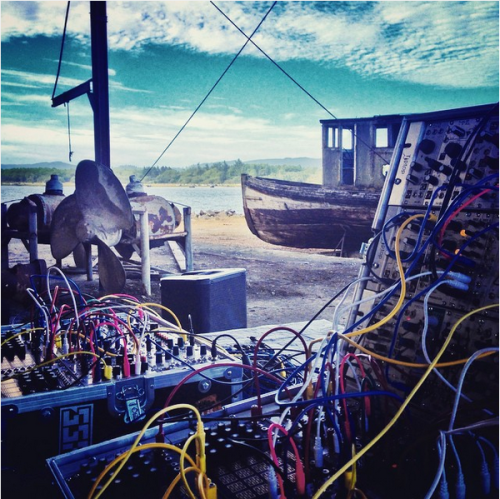

- Robert Henke: Your Limitations Can Set You Free

Dub Techno legend Robert Henke is as celebrated for his co-creation of the Ableton Live DAW as he is for his excellent music. As with many of the producers featured in this list, just about every interview he has ever given is packed full of useful advice for music makers of all kinds but in this video, he shares a tip I have often found especially useful - limit yourself in the studio.

If you’ve ever found yourself in the exasperating situation of being unhappy with a track and throwing layer after layer of sound into the mix in the hope of improving things, this tip is for you! Begin with a small number of elements and add only when and if necessary. Priceless!

- Madlib: Influence Can Be Drawn From All Music

You could spend all day watching practical tips on production, sound design and mixing, and never come close to the level of wisdom imparted by Madlib in this interview. His much-loved Hip Hop sound is an unashamedly eclectic and far-reaching mix of flavours, borrowing samples and ideas from just about every genre under the sun.

In talking about the sorts of music he might play out at a live show, Madlib here shares something I think all creative people can take inspiration from - take your influences from everywhere. Whilst Heavy Metal and Jazz might seem totally incompatible at first listen, given the right treatment fuzzy guitars can sit quite happily alongside a smooth, brushed drum groove. Madlib’s music gives us the compelling evidence that this production philosophy is a profoundly fruitful one.

- Gold Panda: Don’t Overthink Your Arrangements

An excellent tip for those who struggle with finishing tunes (I’m right there with you folks!), UK producer Gold Panda discusses his refreshingly brisk approach to arranging music. Rather than spending hours tweaking every node of every automation curve, Gold Panda takes the view that following your instincts and paying respect to tried and tested song structures gets the job done just as well. Whilst I think there’s a time and a place for tweaking to perfection, I can see how treating your song as successive looped sequences will leave you with a near-finished track most of the time. Suddenly there’s so much more time for the next tune - thanks Gold Panda!

- Flying Lotus: Embrace the Chaos!

My final selection is a tip from one of my all-time favourite producers, Flying Lotus. The prolific producer’s work has touched on Hip Hop, Jazz, Chiptune, Beats and even Prog Rock, so he sure knows a thing or two about getting work done!

In this interview, FlyLo reveals that his Ableton Live sessions are often very messy as his goal is to get the song finished, not create neat and tidy projects. Finding the right workflow for you is what matters above all else, but if you find that you’re spending more time colour-coding regions than making music then I hope FlyLo’s words will spring quickly to mind.

Taken from here - 10 Tips From The Pros | ModeAudio